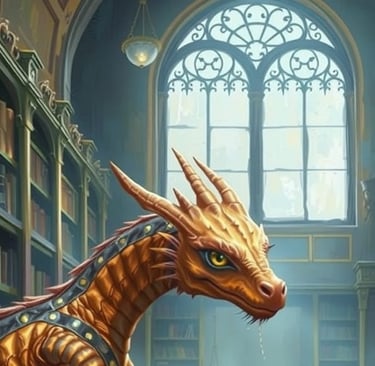

Befriending the dragon: Incorporating AI into academia

Artificial intelligence. Two words that can conjure up wildly different images, depending on the inclinations and imagination of each individual. In any case, it may well be the most seismic technological shift since the Industrial Revolution. And it is not going to go away... - READ MORE

6/1/20254 min read

Artificial intelligence. Two words that can conjure up wildly different images, depending on the inclinations and imagination of each individual. In any case, it may well be the most seismic technological shift since the Industrial Revolution. And it is not going to go away – it is going to keep growing and evolving, becoming more and more ingrained in our personal and professional lives. It makes sense then, to learn how to use it to our advantage as teachers, researchers, and writers. In other words, instead of railing against it, we might do better to befriend this dragon.

To begin, we need to consider the language we use to talk about AI. I have written before about how the words we use shape our perceptions and our reality and this remains important with discussions around AI. The term has taken on a life of its own; scary, impersonal, all powerful, it will take over the world. Outside of tech sci-fi, that’s unlikely to happen. In reality it isn’t ‘artificial’ or ‘intelligence’, or at least not intelligence as we currently conceive it. It began life as a catchy marketing phrase, first used way back in 1955 by a researcher called John McCarthy, who was applying for funding for his interdisciplinary work in computer programming, and the term just stuck.

But perhaps it is a little misleading. Perhaps it is time to reframe the way we speak about AI, that it is not so much ‘artificial intelligence’ as it is a sort of ‘community repository’ of information, insight, and intelligence. It’s just put together in one easy package now; research that once took hours or even days now takes minutes. It isn’t ‘artificial’, it’s real, and it incorporates all the flaws and biases we already have. Crucially, we still have to know what questions to ask and how to weave the answers into our previous knowledge and experience.

We know that our students are going to use AI to write their essays, or at least to help them write their essays. Many of them already do. But the one thing AI is not, is human. It can’t replicate those lively messy classroom discussions. It can’t replicate that ‘a-ha’ moment, when that one idea takes hold in a student’s mind during a heated debate, or how one quiet comment changes another student’s whole perspective. And it is in this juxtaposition that we find the opportunity to embrace new technology while reinforcing the experiential aspects of learning.

So how do we do that? Those of us who have been teaching for awhile likely remember the same sorts of concerns were raised by the advent of Google, and of the ‘paper mills’ where students could just order a paper online, tailored to the specifications of the course. The workaround I have for this is that any work completed outside of classes and labs has to incorporate ideas from the discussions had in class. This keeps our students grounded and attentive – and encourages attendance.

The same concept can be applied with AI. Yes, we should tell our students that they can use AI to help with their essay, but they also have to bring into the paper things we discussed in class. Ask them to how the class discussions connect to their topic. Get them to reflect on how any readings or research they have done, whether with or without the help of AI, helped to grow their knowledge. What did they learn in class this week / month / term that helped them to write this paper? How do those things align? These questions get them thinking about the experience of education, of knowledge acquisition. AI cannot possibly do that.

When it comes to research, we need to speak honestly to our students, to each other, and to ourselves. It’s very easy to just ask Chat GPT or Gemini or Copilot or any other AI program to do research for us. We know that, our students know that. But we also know that AI sometimes just makes things up, just invents articles that don’t even exist. To combat this, we can ask our students to do two things. One is to ask for an annotated bibliography (perhaps following the five-question model discussed in my blog post, Reading for Information Part Two).Theoretically I suppose AI could do that too, although one of the questions does ask for a personal response.

The second thing we can ask them to do is to create a literature tree. A literature tree starts with one academic article (you can even give them a list to choose from), and then the student has to choose an article from the references in the first article, and then one from the references in that (second) article, and so on (best done with between three and five sources). They then annotate each article. Require them to include links to the articles; not only does this mean they have to actually look the articles up, it also helps them to see the evolution of knowledge in their field.

Finally, we need to keep in mind that we, as humans, created this dragon. We dreamt it and birthed it and nurtured it. We as humans have agency to decide how we will continue to develop it. AI can’t know anything that we don’t know. It cannot make new discoveries, although it can help us to make sense of and extrapolate from the knowledge and discoveries we already have. It can certainly compute and collate much more quickly than humans can. It can provide new insights in ways we might not have imagined. Ultimately it cannot find any knowledge that is not already discoverable, but it can help us get there more quickly. Importantly though, we still have to know what questions to ask, and we still have to think critically about the integration of knowledge.

Used with curiosity, integrity, and honesty, this dragon can breathe new fire into the ideas we already have, becoming a tool or even a companion in our learning journeys. And that can only be a good thing.