Shifting Away from Violent Language: Cliches that cause harm

In my blog post “The Futures We Imagine”, I touched on the idea that the way we phrase things matters – for example, we can talk about being ‘pro-peace’ rather than ‘anti-war’. Such shifts in language can have profound effects, helping us to focus on healing and kindness rather than entrenching thoughts and cycles of violence. = READ MORE

5/1/20254 min read

In my blog post “The Futures We Imagine”, I touched on the idea that the way we phrase things matters – for example, we can talk about being ‘pro-peace’ rather than ‘anti-war’. Such shifts in language can have profound effects, helping us to focus on healing and kindness rather than entrenching thoughts and cycles of violence. This month I’d like to explore that idea further: language doesn’t just describe our world, it helps to shape it.

We have all heard the saying “Sticks and stones may break my bones but words can never hurt me.” But I don’t think that’s true. While that particular cliché mostly refers to playground taunts and insults, said to comfort in the same way a kiss fixes a boo-boo, words can cause deep and lasting damage – even when that’s not our intention.

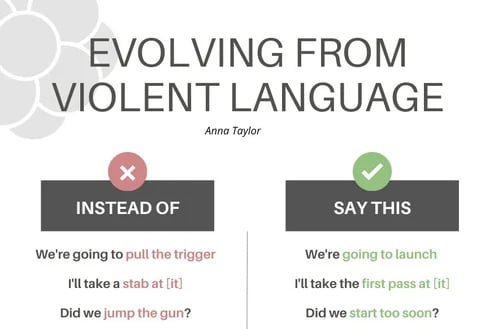

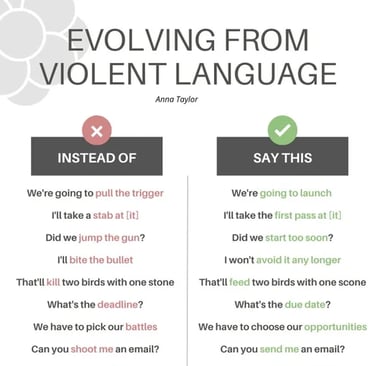

Last summer, I came across a chart titled “Evolving Away from Violent Language”, created by Anna Taylor, who at the time was the communications director and proponent of diversity, equity and inclusion at the U.S. company Phenomenex (I sincerely hope that she has survived the backlash of purges instigated by the Trump administration). It was widely circulated as a meme on social media where it met with both heartfelt approval and dismissive sneers.

My reaction is very much in the ‘heartfelt approval’ camp. Ms. Taylor compiled a list of everyday phrases that use violent imagery and offered kinder alternatives. Here are some examples:

Try “We’re ready to launch” instead of “We’re going to pull the trigger”

We can say “take a first pass at it” instead of “take a stab at it”

Rather than saying we are going to “pick our battles”, we can reframe it as “choosing our opportunities”.

Initially, I shared this chart with two close colleagues, one of whom was so impressed with it that he took it upon himself to photocopy the chart and pin it on every notice board he could find – not just in our department but across the entire campus.

And I understood his motivations. At the time we were researching trauma-informed teaching practices and considering ways to create safer spaces, not just for certain ‘special interest’ groups or ‘special needs’ individuals, but because we do not know what traumas our students and colleagues have undergone. A refugee from a war zone does not need to hear that we are going to “take a shot”; someone who has survived abuse can be shaken by phrases such as “roll with the punches” or that we are going to be “kicking around” an idea.

Seeing the effect this chart had on my colleague, seeing how much it meant to him, led me to start considering how often I used some of the phrases on the list, and how often others did too – which, when you start listening for it, is quite a lot. I pinned that poster in every classroom I used and in my office. I started to catch myself when I was about to say something like “I’ll take a shot at it” and to say instead, “I’ll give it a go”. I began calling out some of my colleagues on the use of violent metaphors as well. Some of them got it, others just rolled their eyes.

But where I really noticed the difference was in my classrooms. Even if your students don’t explicitly notice the words you ‘don’t’ say, you can be sure that they notice what you ‘do’ say. The shift in the classroom culture was subtle, but it was perceptible. Students used kinder language with each other and were more willing to speak up in class discussions. They smiled more. They felt safe.

I came to realize that while a great many of our cliches and common figures of speech raise spectres of violent actions, that doesn’t mean we have to use them. Quite aside from the shift in the classroom climate, there are other very good reasons to actively move towards kinder language – not least because it makes vulnerable people feel safe.

As Stacey R Pinatelli (Psy.D) writes in her article “Language That Deepens Trauma Instead of Healing It”, (Psychology Today, February 28, 2025: https://www.psychologytoday.com/ca/blog/hope-and-healing/202502/language-that-deepens-trauma-instead-of-healing-it): “Healing from trauma is a deeply personal journey, and language is a tool that can either hinder or help. As we interact with trauma survivors, whether in our personal lives or professional settings, it’s important to be mindful of our words.”

The effects extend far beyond the walls of our classrooms or even the borders of our campuses. Words shape worlds, and as educators and writers and just as members of our various social and professional communities, we have a responsibility to think about the worlds we are shaping and to adjust our language to reflect what we want to create.

And after all, we want our words to have an impact. We want people to remember what we have said, to think about it, absorb ideas, learn from them, be inspired by them and take them forward. How much better for that forward movement to be infused with kindness and compassion and for that too to be carried forward.

I don’t always get it right, and even now, a year on, I catch myself slipping towards those cliches – precisely because they ‘are’ cliches. But there is always a gentler way to express the same idea. Try it – you might be pleasantly surprised at the difference it can make.

Next month: Incorporating AI into academia: Befriending the dragon

Shifting Away from Violent Language:

Cliches that cause harm